Charles Maynes

– Cutting Through The Noise –

The Life & Career of Multiple Emmy & Golden Reel Award-Winner, Sound Designer & Recordist, Charles Maynes – Skywalker Sound, Spider-Man, Starship Troopers, U-571, Call of Duty, Tomb Raider

“RipX DAW PRO has become a first call tool for recovering dialogue from noisy backgrounds in a manner that is quite magical. Its separation of human voice in particular, is entirely spectacular.”

Like so many top professionals working in the audio industry, Charles Maynes started playing music as a child. His mother was a pianist, and he naturally rebelled against playing keyboards, instead drawn to drums and percussion. In high school, he started playing in bands which developed into adulthood. But then, in an ironic twist when going to college, he ended up getting drawn to the piano.

“I started working in music shops. First a sort of traditional guitar, bass, drums music store in San Diego, then transitioning to a high-end shop which specialised in synthesisers and samplers, recording studio gear as well as doing repairs. This happened after I purchased an E-mu Emulator II sampling keyboard from them, and started recording my own sounds.”

The owner soon noticed his passion for the technology and was kind enough to let him learn the gear, write and experiment there. This soon opened the door for him to produce sounds commercially for the Emulator 2 and 3 and E-mu Emax, as well as other legendary samplers from Akai like the S900 and S1000.

“I was hired by a soundware company called Invision Interactive where I worked for about 2 years, and created and managed the creation of their CD-ROM libraries for those samplers (mainly the E3 and Akai S1000), and I designed the soundset for a product they made called the Protologic expansion ROM for the E-mu Proteus 1 synthesiser.”

Charles then transitioned to working for Digidesign (later absorbed by Avid) when the development for ProTools started, and worked in customer service. Ultimately he transitioned to the software testing department and focussed on post production products, such as the Post Conform autoconform/auto assembly software package.

“Through the contacts I made in the film and TV world, I was then able to secure a job at Universal Pictures in Los Angeles, who hired me due to my experience gained at Digidesign/AVID, and so my film sound design career was born about 25 years ago.”

Back then, I used to listen to David Bowie a lot, who was always on the leading edge of things. My first real recognition of him was when I was around 10 or so, when his ‘Diamond Dogs’ album came out, and he certainly was a lightning rod culturally in that timeframe. I also loved Peter Gabriel. When he released his album ‘Security’, my mind was fully enraptured. And soon after that, I saw a documentary on him and the making of that album, which was created by the UK television program The South Bank show. He showed sampling sound effects and using them in the Fairlight CMI. This was probably the pivotal moment in my life, as it created my interest both in music technology and sound effects recording.”

“I’ve more recently become a fan of Steven Wilson. He seems to combine so many of my favourite artists and genres into a lovely sort of modern soup blending the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s. I am particularly into his work with Porcupine Tree, and have really enjoyed his solo albums, remixing and playing with bands like Opeth and Jansen, Barbieri and Karn.”

While at Digidesign working in the testing group, Charles immersed himself in the culture of film and TV sound.

“It was sort of my impression that doing sound effects recording was a big part of the film sound editing job, so I would go out and record sound effects whenever I could. Since this was largely speaking a pretty casual hobby, it did further hone the practices I had started to really be attracted to when I was in college, and getting my degrees in TV production and broadcast journalism. Way back then, I had no idea that those skills would apply in the manner that they did going forward.”

Once he’d gotten his foot in the door of the film and TV sound community, he continued to record effects for specific projects, and took every chance he could to go out to record.

“The first big film I did that with was ‘Twister’ where I recorded various odds and ends, but then the most significant sound recording event for me was to record guns in the film ‘Starship Troopers’. Since that time, I established a sort of cache as a weapons recordist, and have over the years recorded weapons, military vehicles and other things for action films and video games ever since.

One project that seemed pivotal in Charles’ career, was being able to contribute sounds to the game ‘Black’ by Criterion software. That had a big impact on the first person shooter game genre.

“I was a small part of an all-star team which ran that project led by Chris Sweetman, (who now is a partner in the company ‘Sweet Justice’) and Ben Minto, who went on to be a Principal Audio Director on the game series ‘Battlefield’ which had a great impact on re-defining what war games sounded like. The film sound world is very much based on word of mouth and networking, so I’ve always tried to expand my contacts and work with as many people as I can internationally.”

As for the person or project that’s had the biggest influence on his career so far?

“I really can’t limit that to one person, as there have been some very significant watershed projects I’ve been allowed to work on. Probably the first (and most humble) was Martin Lopez, who invited me to work on my very first feature film, the B-Movie ‘Return of the Killer Tomatoes’. It was a sort of first step into the film sound universe for me that predated my film work by a decade. The second was certainly being mentored by Stephan Hunter Flick, who really put me on the map as a film sound editor/sound designer. I worked on a number of films with him and treasure his faith in my potential. Jon Johnson, who allowed me to work on the film ‘U-571’, which was the first project I was involved in that won an Academy Award for Best Sound Editing. And finally, my dear friend Ron Bochar, who is a principal at C5 in New York, who allowed me to work on the film Moneyball, which still is one of my very favourite films that I’ve been able to contribute to.

Charles has even worked on a number of games that Treyarch Studios did, the first of which was the bonafide classic, ‘Call of Duty – Big Red One’.

“Tom Hays, the audio director at Treyarch at the time, was impressed with my work on ‘Black’, and invited me to do sound design for the weapons assets for that game. When we did ‘World at War’, Treyarch did a weapons and vehicles shoot for the game, which included all the guns and cannons, as well as vehicles like an M4 Sherman Tank, a Jeep and a German Kubelwagon utility vehicle. I also did some weapons sound design, and worked with a great team including Jerry Berlongieri and Gary Spinrad on the project.

He even worked on the ‘Lara Croft: Tomb Raider’ game, which he cites as a really valuable and fun experience.

“It had roots in the musical sound design era of my career, as well as being my first time working for Skywalker Sound. Steve Boeddeker, who I had met in the mid 80’s when I was doing sounds for the Emulator, also ended up working at Digidesign, and used that as a springboard for his quite notable sound work at Skywalker Sound. He hired me to work on some of the set pieces of the film (my favourite one being the ‘Home Invasion’ of Lara Crofts’ Estate). I did a fair amount of the effects on that sequence including the gun play and it was a very interesting experience, as we sort of approached the design like a music video. As it turned out, Alan Murray also got involved in the project, who would later hire me to work on the films ‘Flags of Our Fathers’ and ‘Letters from Iwo Jima’ which was the second film I helped with that won a Best Sound Editing Academy Award. Alan was a gentleman, and titan in the film sound world, and sadly passed a few years ago.

As for his favourite studio gear and software?

“For hardware, obviously mics and sound recorders are a big part of the work. For mics, some of my favourites are the Sanken CSS-5 (my first really “pro” microphone I purchased) the Crown SASS, and new go to, the Audio Technica 4039 stereo mic which I use a lot in day to day work. For studio gear, I do have a LOT of synthesisers, but the ones that really get used most are probably my 30-plus year old Yamaha DX7IID (which has been used on a lot of my film work) and my Behringer copy of the ARP Odyssey analog synth (which was really the first synth that I learned analog synthesis on). I also have a 2600, a Roland SE02 minimoog clone, and a stack of digital synths I use in music production all the time. I am very much looking forward to acquiring a Sequential Prophet 5v4 synth, which I have longed for for decades. For effects, I have to say that my absolute favourite device is my Moog MF-102 Ring modulator pedal which most recently was used on the film ‘Evil Dead Rising’.

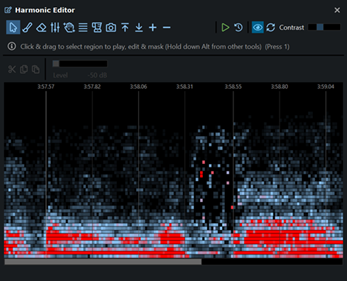

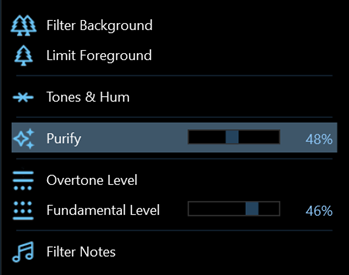

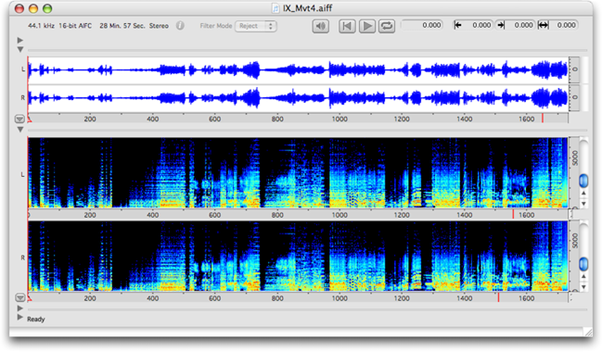

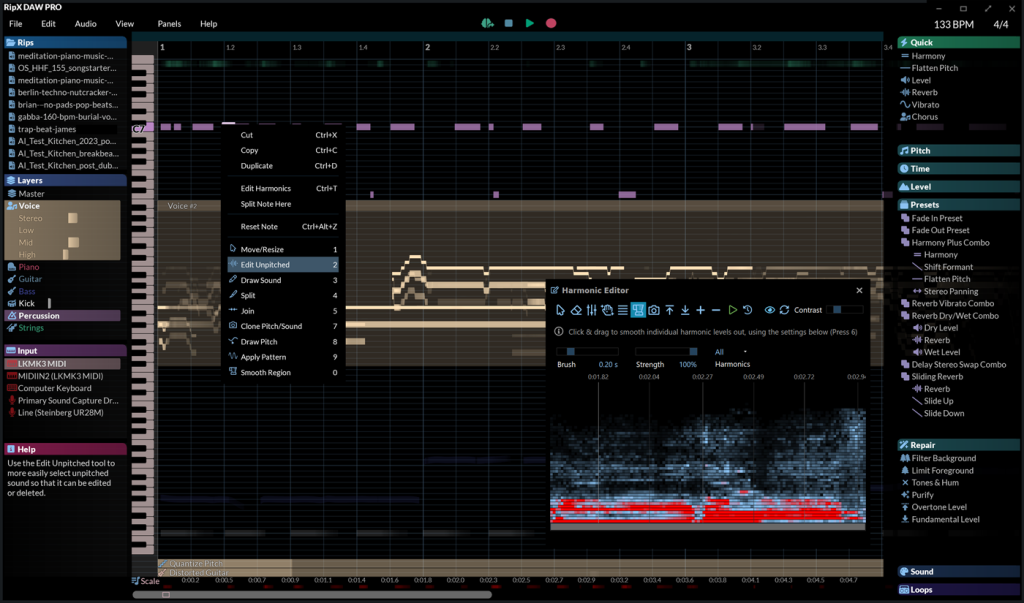

Sound isolation software has always been very interesting to Charles, going way back to IRCAM’s AudioSculpt, and all the way through to the infinite possibilities presented by RipX DAW PRO today.“So much of the time, digging particular qualities from acoustic recordings is a thing we do a lot in film sound design and editing, and using these tools has always provided great possibilities in the process. RipX DAW PRO has been a sort of wonderful expansion on that enterprise through its spectral division of a composite sound, and its very direct, and very easy to use tools allow possibilities that are really not touched by other apps and plugins, many of which are considerably more costly as well!”

“I don’t really use it (so far) in a musical context, but its separation of human voice in particular, is entirely spectacular. I am a relative newcomer to its usage, but so far it has become a first call tool for recovering dialogue from noisy backgrounds in a manner that is quite magical.”

In general, he’s very positive and sees the future of music and audio as entirely brilliant.

“When I first started out in sound, we were using analog tape to record, and there wasn’t even any noise reduction beyond the old (ancient) DBX and Dolby processes to reduce noise on analog recordings using companding technologies, EQ and gating. I think if we look back at the techniques illustrated in Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Conversation’, where Harry Caul would use phase cancellation to make inaudible conversations become audible, the idea that it would be possible to re-envision whole musical mixes in the manner RipX DAW can, would have been seen as some sort of audio witchcraft to classic sound geniuses like George Martin and Rudy Van Gelder in the 50’s and 60’s.”

“A lot of the academic ideas about how that sort of spectral deconstruction were the subject of numerous papers in the Computer Music Journal in the 70’s and 80’s, and now seeing that technology so readily available is a quite remarkable achievement. We also have new spatial possibilities with things like Dolby Atmos, where truly immersive sound presentations are made available to a wide audience, and I would expect that there are many different things which will further emerge, like object tracking of sounds vs picture, and with procedural audio synthesis of natural sound events which will continue to be more refined to the point of being invisible to the listening audience.”

“I think Moore’s Law largely states that all technology moves in an exponential advancement arc. As computing power continues to follow this paradigm, more and more complicated processes will become immediately available and not require sound artists to have to wait iteratively for a result. When I think of the processing time things like AudioSculpt and Tom Erbe’s SoundHack software took to do their magic back in the 80’s and 90’s, we are now seeing far more sophisticated processes be directly possible, and with automated real-time control. Devices such as the Kyma, did magical stuff in near real-time, but at fairly significant cost (and programming effort for their users), and many of those things have been dramatically superseded with far lower-cost software running on dramatically less costly, and more powerful computing platforms.”

“If we consider that ProTools, when I was first working on it, moved from a DSP platform, which provided 4 voices of playback with minimal realtime processing, to today’s iteration of it, which supports over 1000 voices for playback running on native (and low cost) computers, we can see that Moore’s Law indeed is called a “law” for a very good reason.

Finally – for those just starting out in the industry, Charles believes it’s important to always be patient with your creative maturation.

“Overnight success in nearly every field requires a minimum (so it seems) of about a decade of very hard, and focused work. I think it is a mistake to think that technology can substitute creative judgement, and the more creative influence we take in from excellent and considerate art drives us forward more than anything else. The technology has become very powerful, and largely isn’t the gating factor for envisioning creative vision for most people. It is now a matter of fundamental thinking and aesthetics which drives successful outcomes in music production and linear or interactive media production. In the end, it’s about the limits of our imagination in providing compelling art – whether visual, moving images, or sound. We are in the end storytellers, and sweating each detail is very important to the end result. Yes, chaos can have its place in that, but a composition is usually something that needs both discipline, and indiscipline to make it work with insight, and a more lasting impact aesthetically.”

Find out more about Charles Maynes HERE, join his popular Facebook Group HERE and follow his community’s thread on RipX DAW PRO HERE.